The Abolitionist Movement

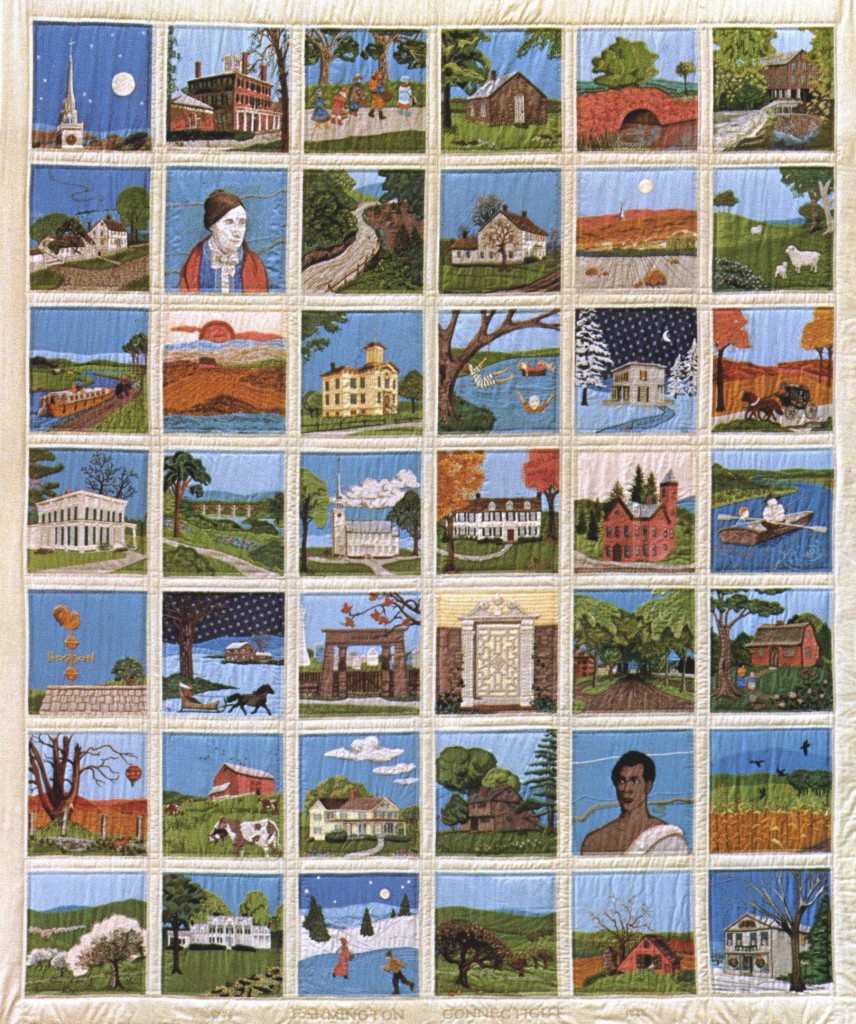

Slavery was legal in the thirteen colonies before the Revolution, but antislavery sentiment grew after the war. The first article published in America that called for the abolition of the slave trade was written by Thomas Paine in 1775, and the first American abolition society was formed by Quakers in Philadelphia in 1775. The society ceased to meet during the war and the British occupation of Philadelphia and was reformed in 1784. Many more abolitionist societies were formed after the war, including A Society for the Abolition of Slavery in Hartford in 1791. Noah Webster of Hartford was a leading member, along with several Farmington residents: Thomas Seymour, Rufus Hawley, Aaron Austin, and the Rev. Allen Olcott.

As a result of the abolitionist movement, some states and regions began to pass legislation prohibiting slavery. The Northwest Territory abolished it in 1787 under the Northwest Ordinance, which stated: “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

Northeastern states gradually adopted laws abolishing slavery or leading toward emancipation. In 1784, the Connecticut General Assembly passed a bill for the gradual emancipation of slaves — all slaves born after March 1, 1784, would be free at age 25. In 1848, Connecticut became the last state in New England to abolish slavery — but even then the law did not apply to slaves 64 years and older. In 1800, a census counted 951 slaves in Connecticut; in 1830, the number had fallen to 25.

By 1812, states that had abolished slavery or taken steps toward emancipation included Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Vermont and Ohio. Slave states included Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, South Carolina, Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee and Louisiana.